The Josephites, more formally known as the Society of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart, are a Catholic order of priests founded in 1893 to serve African Americans. They have been in many ways a pioneering order, one that had some of the first Black Catholic priests in America, a history chronicled in Stephen J. Ochs’s Desegregating the Altar: The Josephites and the Struggle for Black Priests, 1871-1960. It’s an excellent book that should be read by anyone with an interest in Black Catholic history.

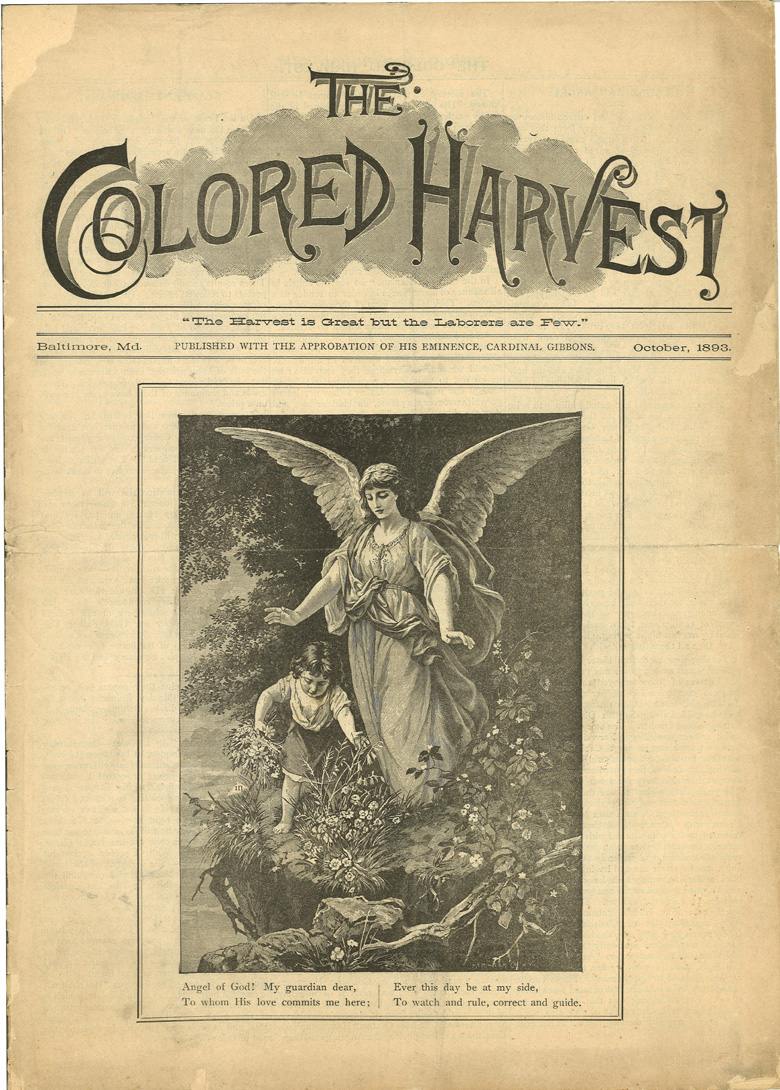

When I had the privilege to visit the Josephites’ archives in Washington, D.C. a few years ago, I found myself drawn to an aspect of their history that Ochs had not especially been, however: their newspaper/magazine, known before 1960 as the Colored Harvest and after 1960 as the Josephite Harvest. I was especially interested in the Colored Harvest during its earliest days, when it was overseen by a Fr. John R. Slattery (no relation to John Slattery, the editor of DailyTheology.org), the Josephites’ first superior.

Slattery possessed somewhat contradictory racial attitudes; he was one of the staunchest (if not the staunchest) advocates for the ordination of Black priests, but he simultaneously held paternalistic and ambivalent attitudes toward African Americans more broadly. I want to focus on the pages of Colored Harvest in this essay both because Slattery’s ambivalent racial attitudes are open display in his writings, and because the paper provides an interesting case study in white Catholic attitudes toward African Americans, both Catholic and non-Catholic, in nineteenth century America.

What would a reader have found in the pages of the Colored Harvest during the time that Slattery ran it? An average issue of the paper was filled to the brim with original articles about African American religious and social issues, along with small reprints from other papers and articles about the Josephites themselves. Most articles are not credited with an author; it is safe to assume in some cases that the author was Slattery himself.

The first issue of the Colored Harvest, published in October 1888, begins with an “Address to the Young Catholic Men of America,” an article that reappears frequently throughout the early days of the publication’s run. It is essentially a plea for young (white) men to come to the Josephite seminary and for subscribers to send funds to enable the order’s work. The piece orients the reader specifically to the order being focused on African Americans:

There are upwards of seven million of the African race in this country, less than two hundred thousand of whom are members of the True Church. More than half do not profess any sort of Christianity and of those who do a great proportion have but low and superstitious forms of the more vulgar Protestant sects. Yet the colored people are naturally intelligent, have admirable moral qualities, and are remarkably gifted by nature with the religious sense, being fond of participating in public worship, easily led to accept the truths of revelation, and have a bright perception of the beauties of a moral and religious life.

The passage was intended to convince readers of the humanity and possibility of salvation for African Americans, particularly those in the American South. While its tone may come off as patronizing and condescending, and promoting stereotypes, Slattery would have perceived this as a full-throated defense of the virtue and morality of African Americans and as a defense against any suggestion that their presence in the Catholic church was unwelcome. The passage went on to describe young men who joined the order as “superior to family, race, caste, and every form of narrowness.” By joining the Josephites as a young white man, you could potentially transcend race itself and devote yourself to the conversion and maintenance of African American Catholic communities.

Articles arguing for black priests were also a crucial element of the Colored Harvest during this period, and were clearly part of Slattery’s agenda to popularize the cause among Catholics. Specific black priests were also set forth as examples of why African American priests were both wanted and needed. For example, a January 1903 article, “Father Dorsey in Louisiana,” argued that African American priests were both wanted by African Americans and essential to making converts and outmaneuvering Protestants. John Dorsey was a Josephite and one of the first black priests to be ordained in the United States:

Sunday morning he [Dorsey] heard all the confessions except one woman who could not speak English, who, however, had gone to him, but he was unable to hear her. This fact alone shows how absurd it is the report that the colored people do not care to go to confession to a colored priest. His short stay here is destined to do much good. The colored people want their own priests, and if we had them I feel confident we should soon convert the South. The non-Catholic colored people constantly remark that the Catholics have white priests whilst they have ministers of their own color. All the people are begging me to keep Father Dorsey here in Palmetto. I think Father Dorsey’s presence has been the means of making a notable conversion here.

Inspirational profiles of black Catholic figures formed a not insignificant portion of material in the Colored Harvest during this period. This included saints like Martin de Porres as well as contemporaries like Augustus Tolton or Charles Uncles (October 1890). The Uganda Martyrs, a group of Catholic and Anglican converts executed in the 1880s, are memorialized within the pages of the Colored Harvest as exemplars of faith (January 1902). St. Martin de Porres was an especially popular figure within the pages of the Colored Harvest. De Porres was put forward as an answer to criticisms about the Josephites and their mission. One article opined that “The objection frequently made to any such work is whether the negro is capable of benefiting by such devotion. The History of Blessed Martin de Porres will be our best answer” (October 1888). De Porres was deemed to be an appropriate example for what African Americans could do within Catholicism, as his mother was a formerly enslaved woman of African descent.

Protestants appear in the pages of the Colored Harvest as a wily foe, constantly ready to outmatch Catholics in the mission to convert African Americans. After a description of the various fundraising efforts undertaken by Protestant groups in the October 1890 issue, the reader is informed that “The Colored Harvest…. cuts a sorry figure beside the thousandth part of the least of these sums.” The Catholic reader is meant to read this and reach for their wallet.

Some material served to reinforce stereotypes of African Americans as simple, emotional, or other negative (or quasi-benevolent but ultimately negative, as in stereotypes about African Americans’ inherent religiosity) stereotypes. One article, titled “The Old Negro’s Proof of God,” had its titular character ask “Jes’ look at de sun an’ de moon an’ de stars. Who make ‘em, I ax you, an’ keep ‘em all goin’?” (October 1890) When this kind of rendering of African American speech is used in the Colored Harvest, the content is generally playing on stereotypes of African Americans as simple and foolish, or in this case, wise but unintentionally so.

These are but a few brief examples of the kind of content found during this era of the Colored Harvest, some of the most progressive racial rhetoric among white Catholics of its time. Some of this rhetoric may still seem progressive to us today, while other parts of it may make us uncomfortable or, as noted at various points, seem to promote stereotypes or seem paternalistic. What elements of our own racial rhetoric may be seen this way by our descendants?

In the future, I hope to do more work looking at the broad run of the newsletter, spending more time on how content changed over time and on how the contradictions of Slattery’s views on African Americans played out within its pages. I am particularly interested in how the paper changed after Slattery (he eventually left the Josephites and the priesthood altogether), how it changed when it became the Josephite Harvest, and how it changed as Black priests became more predominant within the Josephites’ ranks.

Alexandria Griffin is a visiting assistant professor of religion at New College of Florida. She recently received her PhD in religious studies from Arizona State University, where she wrote her dissertation on racial and religious identity in the life and afterlives of Patrick Francis Healy, S.J.

All quotes from The Colored Harvest courtesy of Josephite Fathers Archives, Washington, DC, and University of Notre Dame Archives, Josephite Fathers Records, Notre Dame, IN.

Editor’s Note: This post is part of Daily Theology’s Symposium on Racism, White Supremacy, & the Church. Click here for more information or sign up for our email list below to be notified of new posts!

You must be logged in to post a comment.