July 31st is the feast day of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Society of Jesus (the “Jesuits”). The Jesuits are a religious order, officially founded in 1540 and currently numbering over 18,000 priests, brothers, and men in formation. While they are active in a wide variety of ministries throughout the world, they are perhaps best known for their spirituality and for their schools (in the United States alone, there are 28 Jesuit colleges and universities and 60 Jesuit high schools). Having attended, worked, and taught at a few of these schools, I am grateful for the significant part the Jesuits have played in my own formation and for the witness they bear to a spirituality that is attentive to the deep movements of our hearts, the movements that draw us ever forward along our pilgrimage toward God. In celebration of today’s feast day, I offer five things I have learned from the Jesuits that inspire me along this pilgrimage. These five things are not spiritual objectives to achieve as much as characteristics of the Jesuit “way of proceeding,” the particular practical disposition that directs and motivates the Jesuits to continue ever further into the holy mystery of God.

-

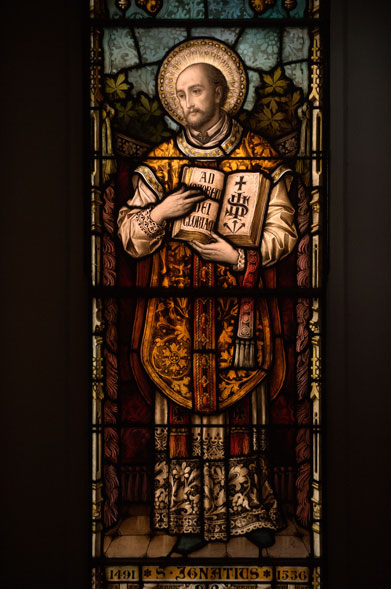

St. Ignatius of Loyola; stained glass window from Georgetown University’s Dahlgren Chapel of the Sacred Heart To look for God in all things: The foundation of Ignatian spirituality is the faith that God is always already active in all situations and contexts. God is here; it is for us to recognize this and respond accordingly. The immediate impact of this conviction is that our everyday life becomes itself a contemplative prayer, described by Walter Burghardt, S.J., as “taking a long loving look at the real.” The prayer fostered by this loving attention to the concrete reality in front us is less like a occasional “long distance phone call” to the heavens and more akin to the continued loving attention we offer a loved one. In the presence of a young child, for instance, we might watch with fascinated joy each and every moment and movement of her young life. We celebrate her very existence and look for insight into the most loving ways we might encourage and inspire her forward. Howard Gray, S.J., suggests that such loving attention engenders reverence and devotion—our response to that which is good and true. Attention, reverence, devotion—all aimed at facilitating an encounter with the God who is always already here.

- To assume the best possible intention of others: Ignatian spirituality grows from the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, a thirty day retreat program ordered to forming one’s attention and appreciation for grace in one’s life and to the quickening of one’s courage to act in ways that are responsive to God’s call. Very early in the Exercises, Ignatius offers to spiritual directors (that is, trained women and men who assist those doing the Exercises) what he calls a “presupposition.” It is necessary, Ignatius writes, to be ever more ready “to put a good interpretation on another’s statement than to condemn it [#22].” Expanding on its specific context within the Exercises, we might come to understand this presupposition as discipline in patience and compassion. This instruction does not require us to naively and blindly accept error or animosity, but tells us that our first step ought to be one of compassion and understanding. Where tension or discord arise, we ought to strive to discern what the other person is actually arguing and to understand the why each of us is taking the position we are. Any and all correction of the other must come, insofar as it is possible, with kindness. Continuing from the conviction that God is in some way mysteriously active in the heart of the other person and that our goal is to be attentive and responsive to divine activity; our most direct route to the truth of the matter at hand travels a path of compassion and understanding.

- To accommodate to the needs and context of the unique person in front of us: Faith in God’s presence in the heart of each person motivates a Jesuit approach to instruction (whether inside the classroom or anywhere else) characterized by meeting others where they are and appreciating the uniqueness of each and every person as a locus of God’s love and activity. God’s relationship with (and call to) each person is unique. This means that we ought to be aware that our way to God is not necessarily the best way for others, and instead accommodate our words to their contexts, allowing for flexibility in all unessential aspects of the message. The Jesuits are not primarily interested in advancing a specific agenda, but rather are focused on the practical question of how we might come to best find God wherever we happen to be. The Ignatian way of proceeding posits that the goal of all our words and actions is to free us from all that hinders the direct relationship between the Creator and the creature [Exercies, #15]. If we believe that God is always already there in the hearts of each of us, the greatest thing we can do is to help others come to recognize this presence within themselves and to be attentive to its subtle prompting towards transformation.

- To present the faith with joy: Since the founding of the order, Jesuits have routinely (although by no means exclusively) emphasized the joy of the Gospel and have charismatically invited deep spiritual and emotive responses of their audiences. While this does not mean that doctrinal precision, moral discernment, or ecclesial rubrics are inconsequential to faith, it does suggest that these ways of approach are not, themselves, the goal. Discussion and debate of theological, ethical, and liturgical language and norms are only fruitful insofar as they lead people toward God, which is our ultimate end for which we are created. Nor, it ought to be noted, is emotion itself a definitive sign of God’s will. But faith in God’s always already active presence in each unique life means that conversion (of all kinds) is made possible when we are drawn—in deep, loving, particular response—to that presence. In his interview with America, Pope Francis reminds us, “The message of the Gospel… is not to be reduced to some aspects that, although relevant, on their own do not show the heart of the message of Jesus Christ.” We cannot spread the Gospel, we cannot bear witness to the presence of God, if we do not do so in joy. “Joy adapts and changes,” Francis writes in Evangelii Gaudium, “but it always endures, even as a flicker of light born of our personal certainty that, when everything is said and done, we are infinitely loved [6].” At its core, the Gospel is a joyous invitation to the conversion of our burning hearts and awestruck minds to be open to God’s grace.

- To go to the fringes of faith: Pope Paul VI observed in a 1974 address that Jesuits have a particular place at the world’s edges: “Wherever in the Church, even in the most difficult and extreme fields, at the crossroads of ideologies, in the social trenches, there has been and there is confrontation between the burning exigencies of man and the perennial message of the Gospel, here also there have been, and there are, Jesuits.” Trust in God’s always already active presence means that there is no place where grace is not tangible and no place where conversion is not possible. And it may very well be for us to respond to the invitation of Jesus by following him to the fringes, the missionary territories (be they geographic, intellectual, or spiritual), and give drink to all those who thirst (for water, truth, or love). It may also mean that we are called to go places were grace is not easily believed, where God is unnamed and God’s word ambiguous, and where betrayal seems more foundational than love. But these places—particularly in the depths of our own hearts—are forever straining to realize the image of God in which we are made. It is an image that is forever proclaiming (in the words of poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J.) that “Christ plays in ten thousand places/Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his/To the Father through the features of men’s faces.”

Ronald Modras observes that for Ignatius and the Jesuits, “God’s spiritual presence so infuses the universe that nothing is merely secular or profane.” Freed from distracting superficiality, we hope to turn to that which is most real, most human, and most part of creation as a way of proceeding that leads us to God. We encounter God by being attentive to the reality in front of us and showing reverence for God’s presence in each of us. This attention and reverence, in turn, encourage the courageous response of devoted love.

And so we pray, with St. Ignatius, that grace might (borrowing from Fr. Jim Janda) pierce those places within us where sinew joins bone and draw us ever on toward an encounter with the love for which we are created.

(this post was originally published July 31, 2014)

Andrew Staron is an assistant professor of theology at Wheeling Jesuit University in Wheeling, West Virginia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.