When I was a junior at Georgetown, I was part of a Bible study on the Gospel of Mark. Although I had been raised as a sort of lackadaisical Presbyterian, I had been trending towards Catholicism for several years (thanks to my Jesuit high school and Jesuit college). I had not yet been baptized, and at the time I was feeling somewhat stagnant in my prayer and faith life. Reading Mark with others, it occurred to me that Jesus’ ministry really began after his baptism, so maybe it was time for me to accept the grace of baptism and get a move on (even in my conversion I was a bit of a narcissist).

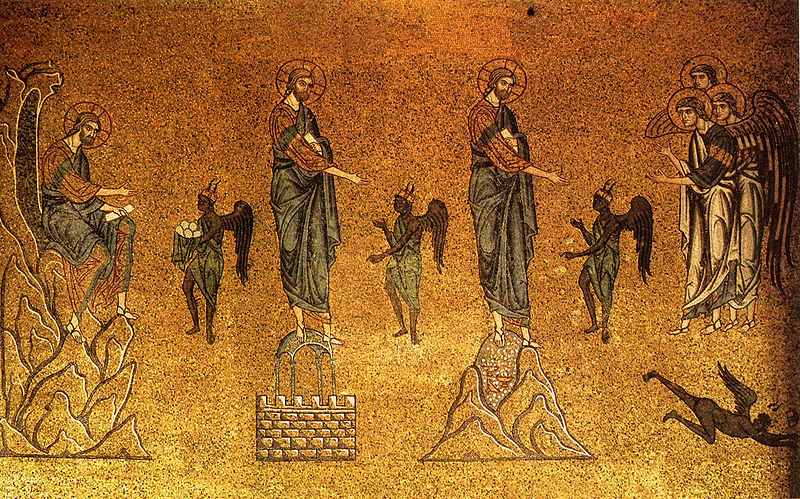

Yet what follows Jesus’ baptism isn’t the beginning of his public ministry, but rather his temptation. And being baptized at the Easter Vigil a few weeks before graduating, I often joked that I too would spend some time in the desert as I headed off to the University of Chicago Divinity School. Surely the heathens there would find all manner of stones for me to turn into bread (critical theory! history of religions!), or would find a high mountain to offer me the kingdom (tenure track!), but I would resist them through the queen of the sciences (theology!).

Again, a touch of the narcissism.

And really, these were not the temptations. What I struggled with then, and what I have struggled with since, is more insidious. Although I can’t claim to say this for all of us who go into academic theology, I know for me it was a choice borne out of my spirituality. I desire to know more about God, about Jesus, about my community, and about my faith. And I think I’m reasonably talented at it – a gift from God, even – so it made sense to me to follow this path. Yet in making an offering of these gifts, I have at different times fallen prey to two particular temptations: (1) impostor syndrome and (2) substituting my intellect for my faith.

First, Impostor syndrome means that I am consistently afraid others will discover that I don’t know what I’m doing. I’m a phony – not a real theologian – and at some point I’ll be found out. Maybe it will be at a conference, or in the classroom, or in an article I submit. The work I do isn’t good enough, isn’t smart enough, and doggone it, people will find out I’m a fraud. Even worse, at times I want to twist this into a virtue – it’s just my way of being humble. But it’s not true humility, because it’s rooted in a misguided, inaccurate understanding of my true self.

You must be logged in to post a comment.