From the editors: this guest post is from Stuart Squires, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Theology at Brescia University. He may be reached at Squires3@yahoo.com, www.stuartsquires.com

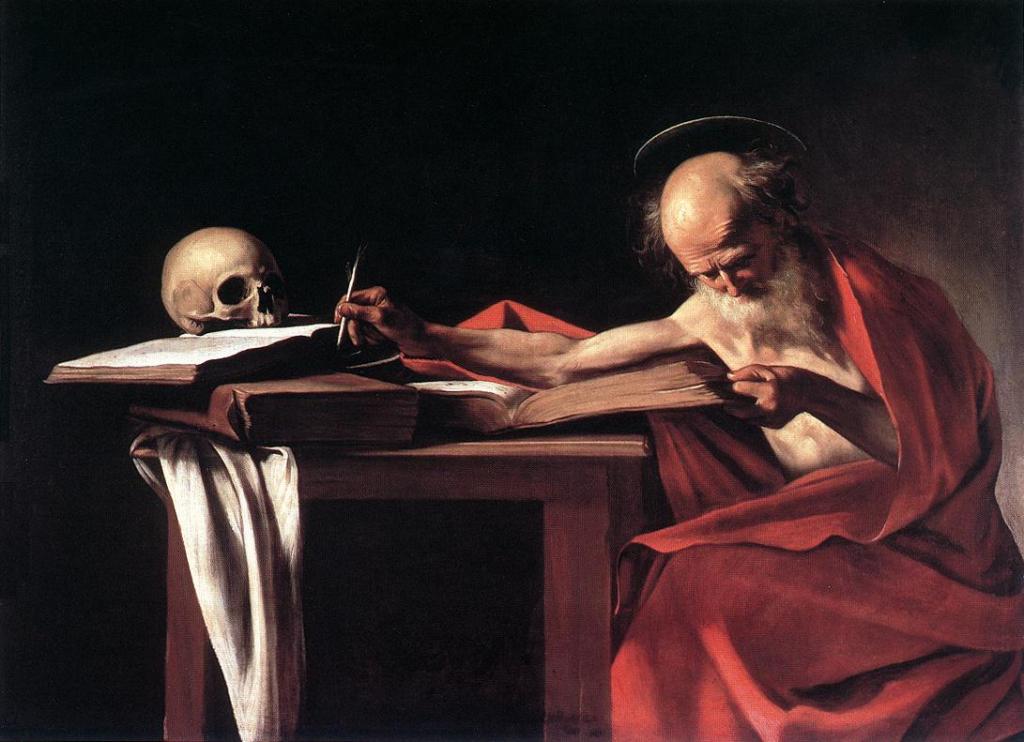

Today, September 30th, is the feast of St. Jerome (ca. 331—ca. 420), who, along with Sts. Ambrose, Augustine, and Gregory the Great, is one of the four Latin Doctors of the Church, and these days, in my opinion, is the least appreciated of the four.

Today, September 30th, is the feast of St. Jerome (ca. 331—ca. 420), who, along with Sts. Ambrose, Augustine, and Gregory the Great, is one of the four Latin Doctors of the Church, and these days, in my opinion, is the least appreciated of the four.

We know very little about Jerome’s early life as no one penned a Vita in his honor, nor did he write a Confessions-style autobiography. He was born in Stridon, but the exact location of this town is unknown.[1] His family’s considerable wealth allowed him to receive the best education in Rome. During his studies, Jerome reports spending his Sundays visiting the martyrs in the catacombs, which profoundly shaped his Catholic imagination.[2]

He bounced around the Roman world for a number of years after his schooling. During a stay in Antioch, he had a fever-induced vision of the Judge at his judgment. Jerome told the Judge that he was a Christian. “You lie!” The Judge snapped in reply: “you are a follower of Cicero, and not of Christ. Where your treasure is, so also will your heart be.”[3] Jerome had preferred refined pagan authors to the vulgar literary prose of the Bible, describing it as “rude and repellent.”[4] Despite Jerome’s passion for literature, he did not read any of the great Roman authors for 15 years after his vision because he was so shaken by the experience.

Jerome eventually returned to the Eternal City where his reputation began to grow as a translator and exegete. He found himself in the favor of Christian elites and had impressed Pope Damasus with his experiences in the east and his knowledge of Hebrew, which few Christians knew at the time. He also became a spiritual advisor to a number of rich, aristocratic women whom he encouraged to embrace the ascetic life by arguing that the good of marriage is limited to the future consecrated virgins who might come from the marital union.[5]

For the last several decades of his life, Jerome lived in Bethlehem where he established a monastery and installed himself as its head. This was a time of prolific literary output and he engaged in many of the great controversies of his day, such as Mary’s perpetual virginity, the role of marriage in the Christian life, and the anthropological fights of the Pelagian controversy, among others. Just a few years before his death, his monastery was burned to the ground by an unknown group of individuals.[6]

For the last several decades of his life, Jerome lived in Bethlehem where he established a monastery and installed himself as its head. This was a time of prolific literary output and he engaged in many of the great controversies of his day, such as Mary’s perpetual virginity, the role of marriage in the Christian life, and the anthropological fights of the Pelagian controversy, among others. Just a few years before his death, his monastery was burned to the ground by an unknown group of individuals.[6]

Jerome is best known for his translation of most of the Bible into Latin from the original Hebrew and Greek. Prior to Jerome’s Vulgate, Old Testament translations into Latin came from the Greek Septuagint translation. Jerome was criticized in his day for his turn to the original Hebrew, including Augustine who wrote to him with less than enthusiasm for the project, saying “I think that they [the translators of the Septuagint] should be given a preeminent authority in this task without controversy.”[7] Despite Augustine’s protests, the Vulgate became standard in the Church in the medieval period, and was declared “authentic,” “approved,” and that “no one dare or presume under any pretext whatsoever to reject it” by the Council of Trent in 1546.[8]

He is also infamous for his verbal onslaughts of other eminent Christians of his time. In his On Illustrious Men, he curtly dismissed Ambrose, saying that “I withhold judgment of him because he is still alive, fearing either to praise or blame lest, in one event, I should be blamed for adulation, and, in the other, for speaking the truth.”[9] In his correspondence with Augustine, who had written to Jerome inquiring about his interpretation of Galatians and was the only person from whom Augustine ever sought advice,[10] Jerome icily responded to him that “there remains for you only that you love one who loves you and that you, a youth in the field of scripture, do not challenge an old man.”[11] Even after the death of Rufinus, his fiercest opponent and one-time friend, Jerome could not resist taking one last shot at him by calling him a “pig.”[12]

It is these types of comments that have led scholars to declare Jerome an “irascible, morbidly sensitive old curmudgeon,”[13] that he “resented adverse criticisms,” [14] that he was “sensitive and easily offended,” [15] that he had a “prickly character,”[16] and that he was “unbalanced.”[17] Although these criticisms may not be far from the mark, it is precisely this side of Jerome—the deeply flawed side—that has drawn me to him.

It is these types of comments that have led scholars to declare Jerome an “irascible, morbidly sensitive old curmudgeon,”[13] that he “resented adverse criticisms,” [14] that he was “sensitive and easily offended,” [15] that he had a “prickly character,”[16] and that he was “unbalanced.”[17] Although these criticisms may not be far from the mark, it is precisely this side of Jerome—the deeply flawed side—that has drawn me to him.

Jerome was not the stoic Athanasius who courageously shouldered his burdens when he was exiled from Alexandria five times by the Arians. When Jerome experienced his own sort of exile after the death of his patron Damasus, he venomously hissed at the “Senate of Pharisees”[18] for having driven him from his beloved Rome.

He was not the continent Augustine who never hinted at struggles with concupiscence after his famous moment in the garden that brought him the chastity for which he had been praying. In his mid-seventies, Jerome tells us that it was only when his body was broken by age that he was freed from his disordered desires.[19]

He was not the disciplined Antony of Egypt who spent 20 years alone pursuing a life of renunciation and who perfected the art of self-mastery.[20] He completely failed at his own desert experiment, even though he had dragged his sizeable library across the Mediterranean to keep him company (what a spectacle that must have been!). Years later, he said of his time there that “when I was living in the desert, in the vast solitude which gives to hermits a savage dwelling-place, parched by a burning sun, how often did I fancy myself among the pleasures of Rome. I used to sit alone because I was filled with bitterness.”[21]

I feel a kinship with Jerome when I think of these passages and as I reflect on my own desert experiences: both the physical desert experience I had in the Sahara for two years during my Peace Corps service, and, more importantly, the spiritual deserts of my life where, like him, I have been haunted by my failures and vices. Because of Jerome, I have come to share Fr. James Martin’s sentiment of his patron intercessors when he says that he can recognize himself, or at least parts of himself, in their lives. “This was the aspect of their lives that I most appreciated,” Martin says, “they had struggled with the same human foibles that everyone does.”[22]

Over the years, I have come to see Jerome not as the cranky, old man often panned by his critics, nor an other-worldly superhero whose piety and moral virtue seem to be much too lofty to emulate (as most saints seem to be to me). Rather, Jerome’s brokenness acts as a mirror and invites me to see that my own brokenness may direct me outward from my parched inner landscape toward God’s ebullient fecundity. For, it was in the recognition of his inordinate desire for the beauty of literature—prompted by his fever-induced vision—that led Jerome to receive exculpation after crying out to the Judge from deep within: “Lord, have mercy on me!”[23]

St. Jerome, pray for us.

***

You must be logged in to post a comment.