Every place, every person, every situation of history in the United States has some connection to the ravages of chattel slavery.[1] As I’ve written about in the past, modern American society was built on the systematic bias against persons of African descent, and universities are no different. Since slavery constituted one of the chief forms of economic prosperity for several hundred years in the young conglomeration of states and territories that became the United States, every modern institution bears a part of the blood and torture of the past. It is, lest I belabor the point, a fact.

This fact necessitates what I would like to call an “active remembrance.” In 20th century Catholic theology, this is sometimes known as anamnesis (via Johann Baptiste Metz), but the phrase “active remembrance” is sufficient for today. An active remembrance takes the past not as something from which one progresses, but as something which must transform who we are. It recognizes that present society has not yet fully come to grips with the horror of the past–in this case, the devastation of chattel slavery–and that, as individual people and institutions, we will not be able to see clearly the road ahead until we allow the past to transform us by the brutal reality that it was.

Thus, on this, the first post of Daily Theology’s week of reflection, I invite you to remember something that is usually just another footnote in the history of my current place of scholarship, the University of Notre Dame. It is my argument today that without actively remembering difficult memories such as this, the temptation to rationalize economic and political progress for the sake of “the greater good” will continue to warp righteous intentions through that vicious, cannibalistic tempest known as progress.[2]

Sorin’s Silence

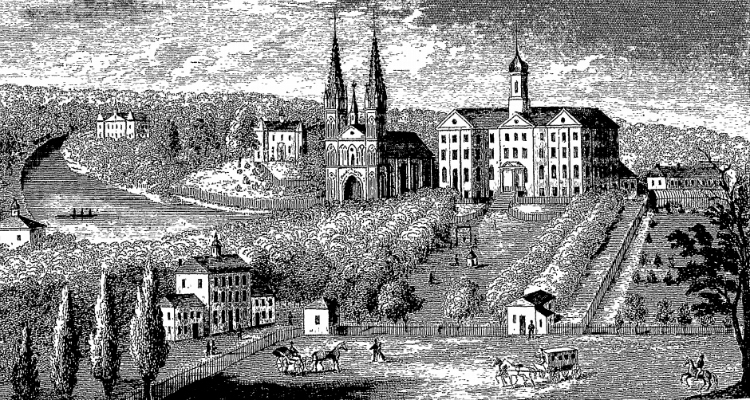

When Notre Dame was founded in the 1840s, its founder, Edward Sorin, CSC, was a strong-willed, single-minded French priest focused on the success of this young Catholic educational institution in the rural American state of Indiana. In many ways, Sorin’s success at founding Notre Dame is remarkable and a test to his economic prowess and political resilience. There is much to honor about the man, and, as such, many honors have been granted him over the last 160 years. In terms of the institution of slavery, however, Sorin was explicitly silent.

Sorin, like many around him, saw danger in political leanings during this volatile time. He actively supported the Compromise of 1850, which is thought to have delayed the Civil War by a decade by giving pieces on each side: e.g., the Fugitive Slave Act was strengthened, but Washington, DC, saw the outlawing of the trade of slaves (though not slavery outright). In a letter in honor of this Compromise, Sorin instructed a protégé, Gardner Jones, to write that

‘The President and Faculty of the Catholic Institution’ of Notre Dame believes the ‘integrity, stability and unchecked progress of this land of religious liberty’ is identified with ‘the highest interests of the Church of Jesus Christ and the highest hopes of humanity.’[3]

The strength of the Union and the promise of progress, wrote Jones, must prevail above all. Other facts support Sorin’s silence: despite a large section of the Underground Railroad operating just miles away in southern Michigan, “there is no evidence that runaway blacks sought refuge on the shores of Notre Dame lakes.” This is not to say, writes Sorin’s biographer, that Sorin “sympathized with bond slavery, but his deepest commitment was, as ever, to the survival and well-being of his mission.”[4]

Sorin’s silence on slavery–what one might call a “middle ground” between the pro-slavery advocates and the abolitionists–found its philosophical support in the popular Catholic convert and apologist, Orestes Brownson, himself a personal friend of Sorin and a large influence on the many of the founding members of Notre Dame’s faculty and students.[5]

For the Good of the Union

From the late 1830s until well after the Civil War, Brownson argued both for the inhumanity of slavery and for the immorality of the abolitionist movement against it.

“We have, ever since 1838, uniformly opposed,—no man more strenuously, whether efficiently or not,—the whole abolition movement, on legal, moral, economical, and political grounds….As a citizen of New York I am not responsible for the existence of slavery in any other state in the Union, and I cannot, further than the expression of my individual opinion, interfere with the relation existing between the master and his slave,

without violating international law, striking at the mutual equality and independence of the states, and sapping the constitution of the Union. The whole abolition movement of the nonslaveholding states as it has been carried on for now nearly thirty years we regard and for nearly the whole of that time have regarded as immoral, illegal, and its abettors as punishable by our laws.”

Browson advocates a third way, arguing that slavery is legal in its municipality, but since it is not a natural or God-given law to enslave other persons, that slave becomes free as soon as it passes into other municipalities:

“They held and hold that slavery may go wherever it is not forbidden by municipal law; we, that it can go only where authorized by municipal law, or municipal usage having the force of law. We are right, and they wrong, if, as we maintain, under the law of nature all men are free, and man has by natural law no jus dominii over man, as all Catholic morality teaches, as was declared by the American congress of 1770, and as is implied in our whole system of jurisprudence, and assumed as unquestioned by nearly the whole modern world. The negro is a man, and has all the natural rights and freedom of any other man. I cannot, as a Catholic, deny this, and am obliged to assert it as a man. The negro is free unless deprived of his freedom by municipal law, or by his own misuse of his freedom.”[6]

Dangers of Rationalization

There were plenty of Catholics who held worse positions than Brownson, and plenty of universities with a worse relationship to chattel slavery than Notre Dame. But such a fact does not excuse the adoption of Brownson’s “for the good of the union” rhetoric, a rhetoric which explains Sorin’s excitement over the compromise of 1850 and his non-participation in the Underground Railroad.

In short, Brownson’s rhetoric argued that practicality takes precedence over justice in this case for the practical purposes of the state and union. But what good is faith if practicality always takes precedent? How serious can one be about the evils of slavery if one does not feel any sort of moral responsibility for those enslaved in the same country?

And yet, the line Brownson walks–and the one that Sorin and many followed–is still followed by many today. There are evils in modern society, though none as great as chattel slavery, that remain unexamined by so many institutions of higher education. How many of us walk the line of Orestes Brownson in our own universities and lives?

“We abhor all sexual assault on campus, but, no, we will not call our culture a ‘rape culture’ and actively campaign against it on campus.”

“We support the Catholic Church’s pro-union stance, but we will not support the unionization of part-time teachers, as such a thing would devastate our financial prospects.”

“We support the whole person, but we must treat students as commodities who should be weeded out as quickly as possible to increase the bottom line.”

“We support the rights of black persons and condemn inequality, but, yes, we will continue to build multi-million dollar buildings and support wealthy housing development plans despite the poverty of the black community that immediately surrounds our institution.”

— – —

I hope to God that not a person reads Brownson’s words and sees rationality and reason. Brownson’s miscalculations betray an assumption of a diminished humanity on the part of those in slavery. Would members of Brownson’s own family have been slaves, I have no doubt he would have campaigned alongside the abolitionists for their freedom.

I hope to God that we can read Brownson’s words and see our own rationalizations for the vicious angels of progress and prosperity that they are. For if we do not, if we fail to see the value of a person as higher than the value of a brick, a program, or a building, then the future of Catholic academia will undoubtedly fall to market pressures, and even the institutions that thrive on billion dollar endowments will lose any public moral standing they may once have held.

— — — —

Editor’s Note: This is the first post in Daily Theology’s Reflection Week entitled, “The University as Social Force: Protest and Activism in Academia.” Follow the link for more information, including upcoming authors.

Notes:

[1] Chattel slavery, of course, being the practice of treating persons of African heritage like animals over the course of several centuries in the Americas. “Chattel” distinguishes this practice from ancient forms of slavery, such as Roman and Greek servitude, typically reserved for those in debt or prisoners of war.

[2] My debt to Johann Baptiste Metz should be clear at this point, as well as to Metz’ inspiration, Walter Benjamin. See especially Metz, Faith in History and Society, and Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History.

[3] Marvin O’Connell, Edward Sorin, 280.

[4] Ibid., 426.

[5] A long line of personal letters between not only Browson and Sorin, but Browson and many other members of Notre Dame’s faculty, describes this relationship in detail, available via the free digital archives of the University of Notre Dame.

To note: Brownson’s philosophical impact on the fledgling university of Notre Dame was overcome, in many ways, by the active anti-racist agenda of Fr. Ted Hesburgh, who consistently sought racial equality on and off campus for decades in the mid-20th century. The university went from being non-partisan in Sorin’s image to actively political and pro-civil rights (quite unpopular in 1951). For an example of this, see Hesburgh’s work with the Civil Rights Commission in Michael O’Brien, Hesburgh: A Biography, 79.

[6] Orestes Brownson, “The Slavery Question Once More,” Brownson’s Quarterly Review (April, 1857): http://orestesbrownson.org/739.html.

You must be logged in to post a comment.