Rev. Thomas M. King, S.J. died of a heart attack on June 23, 2009. Despite the fact that he had broken his hip some seven years prior and had undergone several painful surgeries over the intervening years in a never-fully successful attempt to repair the damage done that day he slipped on the ice, he had continued his service to the Georgetown University community until his death. He had taught a couple of theology courses that previous spring term: Problem of God and Teilhard and Some Theologies of Evolution—the latter course on the theology of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, will undoubtedly not be continued at Georgetown. He had just completed another of his forty academic years of celebrating Mass at 11:15pm six nights a week—a tradition also not to be continued. He was scheduled to teach in the coming autumn. And on May 9, 2009, he celebrated his eightieth birthday.

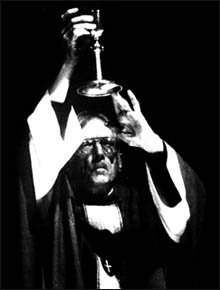

I met Fr. King in 1998. Having failed to get into his Problem of God course, I began attending Mass a couple of nights a week, although I don’t remember exactly why I began going. My attendance ebbed and flowed over the next four years. I was never a regular, yet I met some of my closest friends at the post-Mass soirées—“not just a party,” Fr. King would always remind us, “a high class party.” There was something about Fr. King softly, but intensely, leading the congregation in the celebration of the Mass in the flickering candlelight that made it just a little easier to believe. There was no doubt in my mind that he believed in what he was doing. And he seemed to live his life close enough to all things mystical that he made me want to trust him. He was always fully himself, always faithfilled, always open to the students around him. The more clearly he was himself, the more clearly he was pointing away from himself. I trusted Fr. King, and Fr. King believed.

Try as he did to convert me into a Teilhardian, I was neither scientist enough nor mystic enough to understand what the paleontologist/theologian/Jesuit was doing. However, what did strike me—and strike me deeply at that—was the courage Fr. King attributed to Teilhard. Fr. King painted a picture of a deeply religious man whose faith drove him toward creation itself in a passionate search for the fingerprint of the Creator. Nothing that was true was unrelatable to God and theology. Fr. King himself embraced such a perspective, too. That courage is one of the main reasons I began to study theology and one of the main reasons I have continued to do so. In fact, it was his professorship that I have held, for ten years now, as a model for what I would hope my own career would grow to become. I feel fortunate to have been able to tell him that on his eightieth birthday.

Although I was able to attend the funeral, I missed Fr. King’s wake as I had been returning from France where I had vacationed with my wife and family. In fact, the day he died, I arrived in the city of Lisieux, the home of St. Therese. As I was never drawn to Teilhard, so too, I had never had a strong devotion to Therese. We were there for my wife and her mother, both of whom wanted very much to pay a visit to the Little Flower’s home and her tomb. Fr. King, too, enjoyed Therese’s writing, and discussed her struggles with faith in one of his last published articles, “Endmatter: Believers and their Disbelief” [Zygon, vol. 42, no. 3 (September 2007)]. In the article, Fr. King recounts the struggles that come with the commitment of faith and the experience of emptiness without consolation that marks the lives of so many saints. However, this groaning emptiness may have an echo—a turn to God when reliance upon ourselves proves to be foolish and egocentric. Doubt can allow God to enter. Fr. King ends his article quoting Teilhard: “Our doubts… are the price we have to pay for the fulfillment of the universe.” Therese herself experienced anguish in recognizing the voice of atheism within her heart. While overwhelmed on her deathbed with feeling utterly abandoned by God, she died affirming, “My God, I love you.” I was in the hometown of this little flower as Fr. King passed away.

While in Lisieux, we visited Therese’s childhood home. While there, I was caught off-guard by the fact that they had little Therese’s toys on display. While I had, in the past, seen items that had belonged to saints, such items were often marked by their religious nature: bibles, rosaries, crosses, religious clothing. Never before had I seen a saint’s toy. In fact, I realized that I had never thought of a saint actually owning a toy. I tried to respond to my excitement by taking a dozen photos of her jump rope. Little Therese, her heart full of love and anguish, had a jump rope.

I was thinking of that jump rope during the post-funeral reception at the Jesuit residence. I recounted my surprising excitement to Vincent Miller, a colleague of Fr. King’s in Georgetown’s theology department. He seemed to understand my reaction and gave me words with which to make sense of it. He observed that although the Catholic Church has a very developed sacramental theology, it can stand some further reflection on the sacramentality of the everyday. In our mass-produced, commodified culture, we need a richer experience of the holy in our everyday lives. We need to understand things and words as potential prisms of grace. For me, it was a jump rope and the image of a little girl having fun—a little girl who would grow into holiness. The gauntlet was thrown—if a jump-roping little girl could do it, perhaps the rest of us ought to be thinking more seriously about the source of ultimate meaning in our own lives.

Talk of sainthood continued at a post post-funeral-reception luncheon at a traditional Georgetown restaurant, The Tombs. A group of people had gathered to eat and reminisce and gain comfort from others. After lunch, someone half-jokingly described Fr. King’s possessions as “relics”—a term used to describe items of significance (and body parts) in the life of a saint. My friend, Stephen Feiler—who had been as close to Fr. King as anyone I know—let out a half laugh, “Is Fr. King a saint?” After a brief pause, he responded to his own question. “Well… I guess I don’t have any doubt that he’s in heaven.” And that is, after all, the definition of a saint—someone who is in the presence of God—whatever that actually means.

It is striking to think, “I knew (know?) a saint.” After all, in thinking about my own relationship with Fr. King, I have memories of the mundane along with the sublime. Along with my memories of candle-lit consecrations, I remember his laughter. Along with my memories of his homilies, I remember his silliness as he instructed a retreat in rousing games of “el smasho” or encouraged “night-running.” And along with his lectures on the rigors of faith, I remember: “Abraham got it in his head that God wanted him to kill his son. I say ‘got it in his head.’ You might say, ‘Teacher, it says in the Bible that God told him to.’ Poor Abraham. He didn’t have a Bible.” He was, indeed, quite a character. His particularity stood out. In whatever he did, he was always fully himself. Every lecture, homily, and greeting was characteristically his.

But, in reality for Fr. King, that which was characteristically his was not ever just his at all. It was Fr. King’s particularity that stands out in my mind—but a particular type of particularity, to be sure. In The Analogical Imagination, theologian David Tracy argues that a “religious classic” is any text, image, ritual, or person that can disclose permanent possibilities for meaning and truth. The revelation of the possibility for ultimate meaning is never done “generally”—such disclosure occurs in the only way meaning can ever be experienced or understood—in a particular time, in a particular place, in a particular social context. Things do not mean anything generally. Things mean something to us. Such particularity, when marked by meaning while intensified and rarified, is a gift to all those bearing witness. Yet such giving only occurs when the particularity can be expressed in a way accessible to the witnesses.

Fr. King’s particular ability was to take his particular experience—hinted at in countless homilies and lectures, books and conversations—and make is relatable to his students’ own particular experiences. Along these lines, he once commented to me, in response to my inquiry regarding how he prepared his homilies: “I speak to myself and say what I need to hear. And if anyone else happens to be listening, all the better.”

However, when one’s particularity is defined by a life lived in dedication to God through specific attention to reason, creation, students, and Mass, such a life has the potential to open others to the possibility of such dedication in their own lives. And when one person’s life is defined by love and grace received from God, such a life was the real potential to open others to the possibility that, perhaps, just perhaps, they, too, are so loved. The gauntlet is again thrown—if he could live such a life, perhaps I could, too. Again, the more clearly Fr. King was himself, the more transparent he became and the more clearly he was pointing away from himself to the one he loved so very much—to the one who loves him.

I was surprised by the anger and frustration (and fear?) that prevented me from engaging that possibility. For several weeks after Fr. King’s funeral, I struggled with Mass and with prayer. I was surprised by how deep the hurt penetrated and how unable I was to shine any clear thought on my emotions, let along be able to express them in words. Yet, I insisted to myself that such a reaction would be the opposite of what Fr. King would want. I wondered what Fr. King would have to say to me had I been able to hear him. I thought about turning to Teilhard, but quickly rejected that idea as I still am quite unsure as to what Teilhard is trying to say in general. So I turned to Annie Dillard, the Pulitzer Prize winning author (and another Pittsburg native like himself, Fr. King liked to remind me) to whom Fr. King introduced me in 2001. I re-read Holy the Firm, the first book of Dillard’s I ever read. Finding hints of a response but nothing more, I turned to Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. And while sitting in an examination room at Georgetown University Hospital, waiting for a doctor to come and take a look at my strained knee, I read:

There is not a guarantee in the world. Oh your needs are guaranteed, your needs are absolutely guaranteed by the most stringent of warranties, in the plainest, truest words: know; seek; ask. But you must read the fine print. “Not as the world giveth, give I unto you.” That’s the catch. If you can catch it will catch you up, aloft up to any gap at all, and you’ll come back, for you will come back, transformed in a way you may not have bargained for—dribbling and crazed. The waters of separation, however lightly sprinkled, leave indelible stains. Did you think, before you were caught, that you needed, say, life? Do you think you will keep your life, or anything else you love? But no. Your needs are met. But not as the world giveth. You see the needs of your own spirit met whenever you have asked, and you have learned that the outrageous guarantee holds. You see the creatures die, and you know you will die. And then one day it occurs to you that you must not need life. Obviously [275].

Obviously?

But this radical claim is not radical at all, if placed under the horizon of faith in the God of Jesus Christ. And one who has the faith and hope and love to live in such a way that this claim is made concrete in his words and actions cannot but transform those around him—in a way that few bargained for.

In reflecting upon his work with the students of Georgetown University, Fr. King wrote, “Students know me through both preaching and teaching—and that is how I know myself.” Having heard a fair number of those homilies and lectures, I cannot help but ask myself whom it was, then, that I knew. Fr. Thomas M. King, S.J., made it easier for me to believe. He helped me have the courage to act on that belief. He made it easier for me—and forty years of Georgetown students—to know the holy mystery of God.

These waters of separation, coming to us through the particular everyday, tear us from the everyday and bring us up to something extraordinarily and mysteriously attractive. They tear us from ourselves. They tear us from our former lives and bring us to something new. And sometimes, in carrying aloft one of us in particular, the waters of separation leave upon the rest of us marks that never go away.

You must be logged in to post a comment.